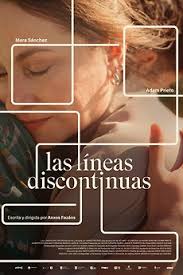

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Dashed Lines (2025) Film Review

The Dashed Lines

Reviewed by: Edin Custo

There’s an obscure, slightly giddy sensation you get on the highway when you cross the dashed line to overtake another car. As a passenger, looking sideways at the people being overtaken, you move through a mix of feelings: a childish “look at us winning this race”, the quick curiosity of seeing the driver and getting a brief glimpse into their life, and the way their sorrows seem weirdly accessible in the creases of a face you’ll never see again. For that brief moment, the two vehicles are peers, running side by side. And then it’s over.

The Dashed Lines, Anxos Fazáns’ second feature, feels exactly like that overtaking manouevre stretched into a film: a brief encounter between Denís (Adam Prieto), an aspiring musician struggling with housing, and Bea (Mara Sánchez), a divorced 50-year-old woman who runs a small music label. Both Sánchez and Prieto honor their characters with performances that stay implicit rather than declarative, opting for subtle, calm and lived-in rather than showy.

Denís is a trans man, but Fazáns refuses to turn that into a “big reveal” or a topic to be debated. It’s simply there: something that lingers in the background, recognsed and accepted without anyone needing to spell it out. In that sense, we are quietly offered a blueprint for how transness might be considered on screen: present, real, unexoticised.

The way Denís and Bea meet is almost absurdly unlikely. When his friends peel off from the nightclub, Denís tags along with a loose afterparty crowd that breaks into a house. As they set about wrecking it, he drifts through the rooms, dazed and just trying to find a spot to sleep. In the chaos he comes across some money and slips it into his pocket, a malicious temptation he gives in to. At the back of his mind sits another decision he can’t quite face: whether to follow a friend to Berlin, a move that’s as financially out of reach as it is attractive.

By the time Bea comes home to her bohemian house, it’s wrecked and there’s a stranger dozing inside. Her reaction is surprisingly mild, more baffled than furious, given the circumstances. Confronted by the lawful tenant, Denís leaves, still with the money. But self-reproach doesn’t allow him to stay that version of himself for long. He comes back, returns it and ends up staying to help Bea clean up.

Her home, rendered with such warmth by Sandra Roca’s camera, feels like a third presence. A deeply lived-in space packed with books, record players and small domestic details that complete the performances: shelves full of volumes stuffed with notes, little papers and cards tucked into records, pressed flowers and scraps of handwriting hiding between pages. It’s also a space under threat. The house technically belongs to Bea’s husband, and while he’s eager to sell it and finalise the divorce, letting go of the place where they raised their daughter is a hard pill for her to swallow. The boxes, the half-empty shelves, the piles of records waiting to be sorted or discarded give The Dashed Lines a constant undertow of loss.

As Denís and Bea clean, they circle their problems, dance, listen to records and drink wine; stray glances and small gestures build a quiet charge between them. Their sorrows are very different, yet there’s something oddly harmonious about them when they share the same space. That’s part of the film’s quiet fascination: how much comfort can emerge between two strangers who happen to find each other at their own crossroads.

At one point, Denís picks up a record and a note from Bea’s long-ago boyfriend slips out. In it, he writes: “In a few days it will all be ready. There’ll be a full moon and we’ll cross the line. We’ll overtake and go off the side. Whatever happens, you know you’ll always find us on the dashed lines.” The image of the dashed lines returns here, not as a slogan but as that in-between strip of road where you leave one lane without yet belonging to another, a space of risk, impulse and small acts of deviation.

Fazáns never fully fills in every backstory. We don’t get all the details of Bea’s marriage, or the complete texture of Denís’s friendships and the Berlin plan. Many of those histories stay suggested rather than spelled out, like that brief pass alongside another car on the highway; close enough to register the other person’s existence, too fleeting to know everything. At times, the restraint can leave you wanting a bit more, but it also feels true to the encounter being staged.

What remains is the feeling. The Dashed Lines is modest in scale but rich in mood: a warm, music-filled ephemerality shared by two people who, in all likelihood, will never be central figures in each other’s lives again, but who carry the imprint of that meeting with them afterwards. Like the memory of a face glimpsed from a car window, it’s brief, a little blurry, and strangely persistent.

Reviewed on: 21 Nov 2025